Technology, uncertainty and change – A turning point for the US biostimulant industry?

Those who follow the US agriculture sector are constantly seeing news about innovations coupled with partnership and acquisition announcements. It can be hard to distinguish technological breakthroughs from hype. We hear swirling promises, feel lingering uncertainties, and yearn for demonstrated technological proofs. How do ‘cold hard facts’ really affect the commercial trajectory of a new class of innovation? And how can investors and industry players ‘read between the lines’ to understand what’s going on?

Some of the hottest areas lately pertain to artificial intelligence and data, biopesticides and biostimulants. Artificial intelligence is relatively early on the adoption curve, with only 8% of analytics projects becoming operationalized. Biopesticide innovation has been happening steadily for generations, yet represents only 4.5% of the global pesticide market. Biostimulants, defined as a yield enhancing crop input that includes a mode of action distinct from plant nutrition, combine aspects of hype and newness with relatively low contemporary adoption. They provide an interesting case study about technology, uncertainty, and change in the modern US agricultural system.

Biostimulant market status

The biostimulant innovation market comprises monopolistic competition. Monopolistic competition is characterized by easy market entry, high non-price competition and product differentiation. Seventeen of Dora’s top 20 biostimulant providers are small cap or startup enterprises and at least 39 commercial players have been identified by IDTechEX. Most of these providers have 2-10 products, comprising a limited IP set within each company.

In contrast, the US agricultural input market shows oligopolistic characteristics. The retail share of US market for farm seeds, chemistry and fertilizer is 57% for the top 4 companies and 90% for the top 10 (AgroPages, 2019). Similarly, for the seed and chemistry input providers, there are 7 retailer-distributor players supplying 70% of the market share (CropLife, 2019). While some of these companies have biostimulant discovery pipelines, small players are innovating most of the new products.

Mergers and acquisitions

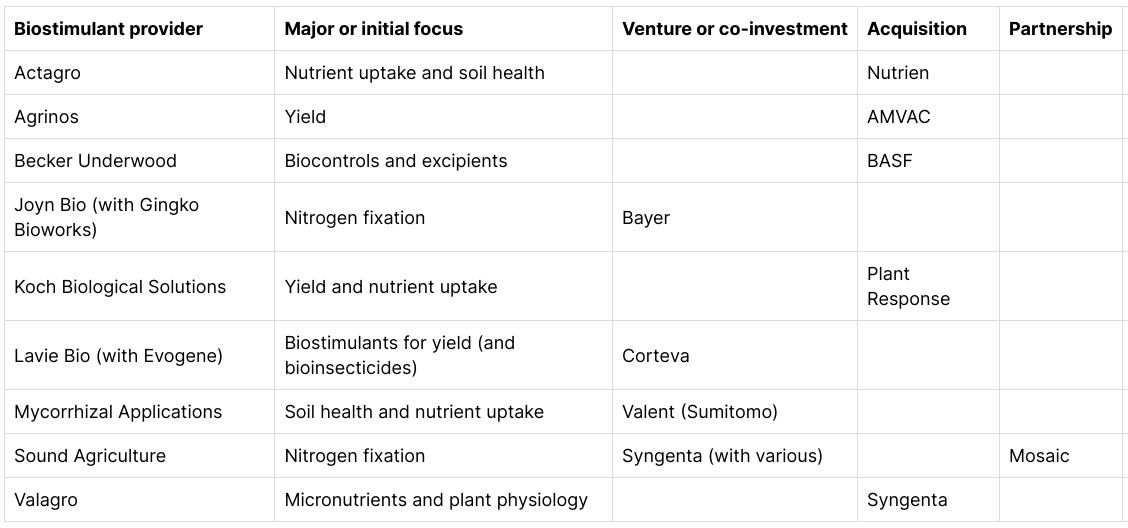

In the last two years, large and medium-size crop input companies have acquired biostimulant startups, including the acquisition of Valagro by Syngenta and Agrinos by AMVAC (Table 1). Additionally, relatively low barriers to entry facilitate direct to grower startups including Meristem Crop Performance and FBN, who are positioning pipelines and private label biological products, respectively, to enhance plant and/or soil health.

Table 1: Sample of noteworthy biostimulant ventures, acquisitions, and co-investments over the past 10 years.

These changes follow economic model predictions that big fish – small fish dynamics like those of the present in this market incentivize mergers and acquisitions. Assuming perfect information, acquisitions create opportunities for synergy, market growth beyond the core business and an opportunity to reap anticompetitive profits. Ironically, imperfect information regarding the technology (i.e., hype) tends to inhibit the benefits of a merger while simultaneously incentivizing it (Hamada, 2011).

Biostimulant expectations began to sober in 2021

Most of the recent activity (Table 1) came before an apparent contraction in the market and dampened market expectations (Figure 1). A sample of 10 market reports over the last five years previously suggested significant market presence and double-digit year on year growth. More recent market reports have sobered in their market size estimates, and dwindled growth rates closer to the overall market growth rate of 3%.

Figure 1: Vector plot of biostimulant market size reports. Each line represents a unique report, anonymized per its publication date. The X origin represents estimated market value at the time of publication. The X end represents the market size projection to the year corresponding to the Y axis. More horizontal line orientations indicate higher expected market growth rates (bullish), and more vertical lines indicate lower expected market growth rates (bearish).

Survey data paints a similar picture. In the last three years, the numbers of retailers selling biostimulants has remained flat. In contrast, the same survey indicated 99% plan to keep or increase their biologicals offerings. The discrepancy between vendors and expectations indicates some retailers are optimistic about biologicals, while others are holding back. Those not moving forward with biological offerings may lack trust in the technology, or struggle to position it in a way that creates value across the value chain (CropLife’s 2021 Biologicals Survey).

These changes in biostimulant market expectations are not obviously related to changes in regulatory, public demand and financial macro variables (Xie, 2021). Instead, the drop appears to be a reconciliation between unachieved promises and unrealized revenue outcomes: the net adoption of this technology did not meet prior bullish expectations.

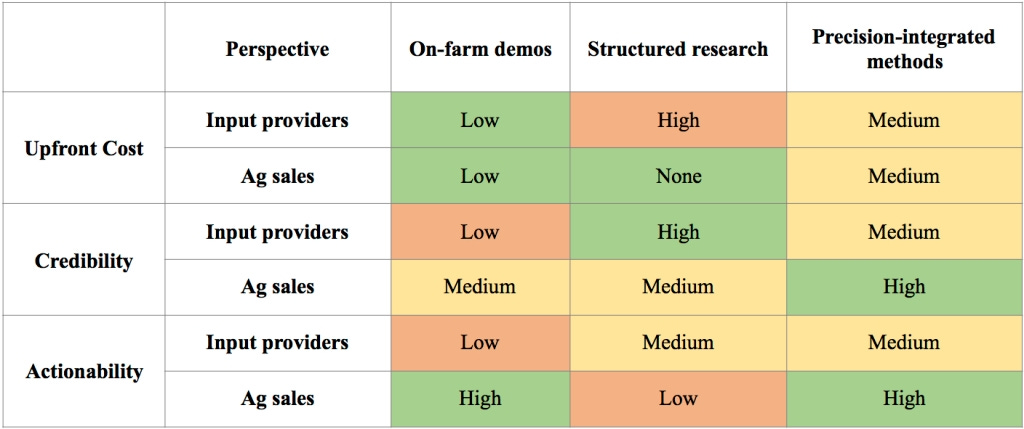

Technology demonstration strategies

Innovators and retailers employ three broad tactics to position biostimulant data to the agricultural value chain. These are on-farm demos, structured research, and precision-integrated methods. Though not exclusive, most biostimulant innovators tend to emphasize one of the three over the others. These tactics have positive and negative aspects that depend on the goal and the audience (Table 2).

Table 2: Comparison of biostimulant technology demonstration strategies in terms of cost, credibility and actionability, for Input providers (e.g., biostimulant innovator, potential acquiring companies) and Ag sales perspectives (including growers, grower-facing companies, and support roles). Color code: Green = favorable, Orange = unfavorable, Yellow = in the middle.

On-farm demos

On-farm demos are the least rigorous and least expensive way to position biostimulant technology. However, this strategy faces a major credibility issue, especially with industry giants (i.e. the top crop input companies) which tend to be highly reputation conscious. While most industry experts discount this data, especially from single trials, growers often make purchasing decisions based on them. Retailers therefore support grower demos, and usually ingest summary statistics (“over-unders”) at the end of the season to inform internal product performance assessments.

Structured research

Structured research includes mode of action assessments and replicated small plot trials. Respected biostimulant innovators typically invest hundreds of thousands or millions (US$) to support a reasonable portfolio. Ironically this outlay has little direct effect on purchase decisions since growers tend not to put stock in reproducible but inadequately representative tests. Because input providers give intensely high credence to structured research outcomes, they can nicely position biostimulant innovators for acquisitions or product licensing.

Precision-integrated methods

Precision-integrated methods combine on-farm applications with data science. This takes shape as variable rate applications, add-on treatments (e.g. co-applied or embedded products), and ‘real world evidence’ comparisons. Precision methods have considerable upfront costs: Growers need to buy specialized equipment, and input providers or retailers need to invest in co-formulation, registration, or data science initiatives.

Enabling technology adoption through yield insurance models

More groups along the value chain are investing in precision-integrated methods for two reasons. First, those who can afford the upfront investment reap longer term credibility and actionability outcomes. Second, this capacity forms the basis of a novel commercial model sometimes known as ‘the yield guarantee.’ This model operates like insurance. There is a yield target. Growers follow a precision-integrated formula based on technical agronomist recommendations. Grower facing companies (or input providers) internalize the input cost. The yield insurance business model therefore incentivizes adoption of low effect but profit-positive crop inputs.

Adaptation to new expectations and adoption of technology development models

Biostimulant innovators seeking to maximize market value should mirror their technology demonstration strategy to those of their intended audience. If they seek to sell direct to grower, or to license to or be acquired by a retailer-distributor, on-farm demos or precision-integrated methods should be prioritized. Those who target input companies may also choose precision-integrated methods or opt to emphasize structured research later into their product development cycles.

Precision integrated technology has moved past lead users and has attained considerable adoption across crops and geographies. Limitations to its application to crop inputs like biostimulants include the barrier to entry of precision delivery hardware, and difficulty operationalizing analytics through software.

Precision delivery hardware

The acquisitions, partnerships and co-investments from Table 1 sometimes mirror similar activity in the precision space.

For example, FMC’s biological landing page also features a discussion of precision agriculture. “These capabilities will also allow for optimal use of FMC’s growing biologicals and synthetic product offerings.” On the acquisition of Agrinos, BusinessWire quoted the President and CEO of American Vanguard: “These biostimulant products are tailored perfectly for use in our SIMPAS® prescription application system.”

The growing investment of input companies in precision delivery hardware substantiates the growing interest in precision-enabled methods to actualize input technologies like biostimulants.

Operationalizing analytics through software

Although ample data is available in agriculture, agricultural researchers have found it difficult to glean meaningful insight from those data sets. This is especially difficult for biostimulants, whose magnitude of effect pales to the variability of typical field environments. This paradox is compounded when effectiveness is dependent on a specific stress or microenvironment:

“Syngenta has also seen differences in responses to biostimulant use in field trials, although Dave King [Head of Technical at Syngenta] acknowledged that sheer scale and complexity of the company’s latest research makes defining specific stress factor effects harder to pinpoint.” (Syngenta UK press release).

Nevertheless, strides are being made. FBN offers data science expertise to analyze product performance from on-farm trials. Sound Agriculture, which previously emphasized win-rates and ROIs, launched SOURCE Performance Optimizer which presents predictive efficacy given soil characteristics. Analytics heavyweight SAS is leveraging its industry-leading multimodal machine learning system to develop crop insurance-based models to predict input performance and optimize application decisioning.

Concluding remarks

If the ‘lies, damn lies, and statistics,’ quip rings true, you might have had an experience that didn’t match a claim bolstered by statistics. The dissonance between ‘the science’ and ‘the reality’ is common also in business to business transactions (Figure 1, Table 2). Given the right market conditions, imperfect information about technologies can foster merger and acquisition activity (Table 1). One remedy to imperfect information is to scrutinize the strengths and weaknesses of how companies position their technologies and for which audience (Table 2).

It may also be worth keeping in mind that ‘now’ may be the wrong time for the right technology. Judging by the widespread inability to enact precision-enabled insights prior to 2021, the heyday of biostimulant innovation (2016 to 2021) may have come somewhat before its time. While a 2% yield increase may not have been sufficient to incentivize a grower based on a return on investment model, it may be ample to incentivize for the value chain based on a data-driven actuarial insurance model.

This biostimulant economic case study should remind us of a principle articulated long ago; change is constant and functions as part of its greater whole:

“We must remember that that agricultural research is not a static thing. Many of the problems of farm production are so intimately bound together that when one factor is changed, the whole system may be changed. Limiting factors under one system of farming may be eliminated, but new limiting factors may develop as the result of a new discovery.”

W. V. Lambert, “Science In Farming,” 1947

© John Gottula, July 2021

Bio

Dr. John Gottula is an AgTech innovator with an applied crop science background and a passion for analytics. John is the co-creator of #AgileAg, a movement to link Agile processes with crop science to drive analytics adoption in the agriculture sector. Join the conversation with John on LinkedIn.